In 1934 the young publisher Allen Lane was in Exeter, waiting for a train. He had been visiting his friend Agatha Christie and was in search of a good book. There was nothing suitable in the station — only trashy novels with lurid covers. He had an idea: people should have access to good quality books in paperback form, costing no more than a packet of cigarettes. His goal, he later said, was “missionary and mercenary”.

The result of that idea, Penguin Books, was launched the following year and is now the most famous publishing house in the world. Its authors include George Orwell, Virginia Woolf, Zadie Smith, Marian Keyes and Philip Pullman. The global brand, Penguin Random House, recorded revenues of €4.9 billion last year, 10 per cent of which came from British sales.

It has been a remarkable success story, and Penguin has gone all out for its 90th birthday, holding a Nothing Like a Book festival and an exhibition at No 11 Downing Street. A birthday bash at the Design Museum in London welcomed the biggest names in books.

But the celebrations may have been dampened. On July 5 The Observer ran an investigation into The Salt Path by Raynor Winn, which was published in 2018 by the Penguin imprint Michael Joseph. Key elements of the story — how Winn and her husband, Moth, became homeless and the severity of Moth’s disease — appeared to have been fabricated or exaggerated. Penguin responded to say that it “undertook all the necessary due diligence” and that the book’s contract included “an author warranty about factual accuracy” — in other words, that the blame lay with Winn. This month the publisher announced that it had postponed the October publication of Winn’s next book, On Winter Hill.

I asked Tom Weldon, the chief executive offcer of Penguin Random House UK since 2011, if there was anything more the publisher could have done. “We publish 1,500 books each year, and it’s literally just a handful which might spark debate,” he said. “It’s something we’ve successfully navigated across our 90-year history and is part and parcel of the publishing industry: books will, and should, drive discussion.

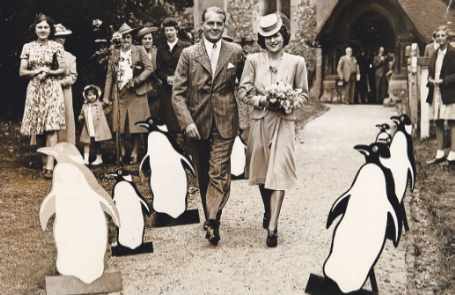

Founder Allen Lane thought penguins had ‘a certain dignified flippancy’

“The conversation around memoirs is not new,” he added. “They are often navigating complex emotional terrain, and the publishing process is based upon a mutual relationship of trust between the author and editor. In this case I am completely confident that our editorial and legal processes were — and remain — entirely appropriate and robust.” It is not the first time Penguin has had to deal with scandal, from fatwas to obscenity trials. I looked back to its beginnings to find the flashpoints that made it a globally recognised name.

My journey began not in the company’s shiny Vauxhall offces, but at Bristol University, the home of Penguin’s offcial archives. The head of brand, Zainab Juma, showed me the first ten sixpenny paperbacks, with their signature orange covers and cartoon penguins. (Lane chose the bird because he felt they had “a certain dignified flippancy”.) These first books ranged from Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms to Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Links.

Penguin’s early days were uncertain. The company struggled with its small profit margins — the only offce it could afford was the damp crypt under Holy Trinity Church, Marylebone. Books were taken up in a lift that used to carry coffns, and the team used a communal lavatory in the form of a tin bucket.

The Second World War made Penguin a trusted British brand (it published guides to aircraft recognition and fruit growing, and started an armed forces book club), but it was a scandal that made it a global success.

Is Lady Chatterley’s Lover a book you want your servants to read, the jury was asked

In its original form, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, DH Lawrence’s novel about a married woman who has an affair with her husband’s gamekeeper, was full of foul language, sex and shocking views on class, love and marriage. Another publisher released an expurgated version of the book, but Lane believed the British public deserved the whole thing. In 1960 he published a “complete and unexpurgated” version.

There was only one problem — the year before, the Obscene Publications Act had been passed, which made publishing something this filthy illegal. Copies hadn’t even hit the shelves when Lane was called back from his holiday in Malaga with the alarming telegram “LEGAL ACTION IMMINENT STOP ADVISE YOUR IMMEDIATE RETURN”.

Penguin assembled critics, bookselling magnates and cultural commentators, hoping that they could prove that the book deserved to be published based on its literary merit. In his opening speech the prosecuting counsel Mervyn Griffth-Jones asked the jury: “Is it a book you would have lying around in your own house? Is it a book you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?” This changed the whole tone of the trial. It became about more than obscenity; it was about a ruling class who continued to patronise women and working-class people.

Penguin’s victory was “a rocket fuel moment”, Juma says. Vast queues formed outside bookshops. It took multiple printers to meet the initial demand for 300,000 copies — and Lady Chatterley’s Lover went on to sell three million copies in total.

Even after Lane’s death in 1970, Penguin has defended books it believes deserve to be read. To this day the publication in 1988 of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses divides audiences. It prompted large-scale protests, a fatwa against Rushdie and Penguin and, in 2022, an almost fatal attack on the author.

Would such a book be printed today? “What we encourage our editors and publishers to do today is to have very robust, honest, open conversations about what books they’re going to publish,” Weldon says. “If they are convinced there is an editorial justification, they should stick to their guns. And yeah, I genuinely think we still do that.” He points to a range of authors from Greta Thunberg to Jordan Peterson as proof.

Others might disagree. Some new publishing houses claim to publish the books that big companies won’t touch. Swift Press, an independent press founded in 2020 by Mark Richards and Diana Broccardo, published Richard Reeves’s Of Boys and Men in 2023.

Richards said that the book — described by the Sunday Times reviewer as “one of the most important non-fiction books of the year” — had been turned down by others, worried that its take on the problems that men face would be considered offensive. Did Penguin miss a trick — and what else is it missing? The basement in Bristol is a treasure trove of Penguin books, many from Lane’s personal collection. Scouring the aisles, I found it remarkable how many I recognised — not just ones I’d read at university, but the Roald Dahl editions I loved as a child, cookbooks from my grandmother’s kitchen and the copies of Shakespeare my greataunt passed down to me. Like the royal Christmas speech, Penguin has become such a feature of British life you almost forget it’s there.

Will it still be here in another 90 years’ time? This is the age of distraction, where attention spans are decreasing and people are turning to social media for entertainment. The National Literacy Trust has found that the number of children and young people who say they enjoy reading has fallen by 36 per cent.

I put this to Weldon, who nods.

“We have a special responsibility to try to address some of these structural challenges. We’ve led some really impactful campaigns to try and address this, not least Libraries for Primaries, where we’ve put libraries back into primary schools in conjunction with the National Literacy Trust. And this goes back to Allen Lane, because he said that reading shouldn’t be for the privileged few.”

Arguably the future’s greatest threat, though, is AI. Technology companies are using published books to train AI models without authors’ consent and Penguin is fighting for the proper enforcement of copyright laws intended to protect human creativity.

“We need to win that battle with government,” Weldon says. But he isn’t entirely pessimistic. “If used responsibly, AI could be an enabler, and it could elevate human creativity if it reduces some of the repetitive tasks involved in our business.”

As AI becomes an ever-more invasive feature of our lives, people want to know the books they read are true. Will the Salt Path controversy erode trust in the brand? “Penguin’s reputation as a publisher has not been built overnight,” Weldon says. “Instead, we have gained the trust of readers through the quality books we put into the world, which have brought joy, new ideas and learning to many. In a world where anyone can publish anything online, books remain essential as authoritative, expert and humancrafted content.”

It would be easy to look at Penguin’s challenges — the Salt Path fallout, addictive algorithms, artificial authors — and fear for its future. But Weldon is confident. “So many people predicted the death of the book 20 years ago. And actually we’re in a pretty good place, particularly compared with newspapers and magazines … So do I think it’s going to be the death of the book? Absolutely not. I think human creativity will always flourish

No comments:

Post a Comment